Ankit Srinivas/BBC

Ankit Srinivas/BBCLast year, after a fatal shooting by a six-year-old girl in India, her parents selected several people in the country – donating her organs. Despite being expected to surpass China as the world's most populous country this year, India ranks 62nd in the global donation league table. The BBC traveled to Rome. There, 30 years ago, the campaign was triggered by the death of another child's gun, allowing us to show how progress progressed.

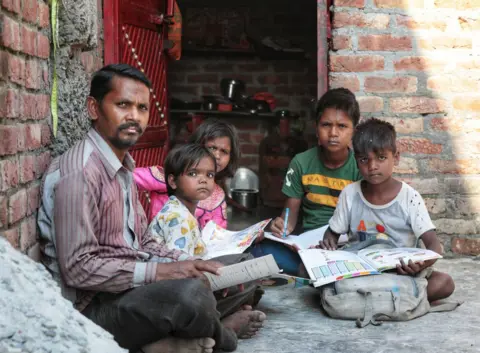

Rolly Prajapati was sleeping peacefully in a house she shared with her five brothers and sisters in the outskirts of Delhi last April. In the next room, her parents were preparing dinner when they heard a loud cry.

As they entered the room, Rory cried out for her parents before falling unconsciously.

It was only time they saw blood dripping from her right ear that they realized something terrible had happened.

Ankit Srinivas/BBC

Ankit Srinivas/BBCRory was rushed to the hospital and immediately declared brain dead. Noida police told the BBC that “there are no clear suspects,” but they continue to investigate.

After days of suffering, her parents decided that they had never done anything before in India. Donate her organs. Rory became the youngest donor at All India Medical Institute (AIIMS) in New Delhi.

Her father, Harunayan Prajapati, explained that the decision to donate the organs of a child is not always easy.

Ankit Srinivas/BBC

Ankit Srinivas/BBCHe said: “I didn't know what to do. I kept thinking all night. I said [doctor] It took me more time to think about it.

“In the end we decided to move on.

“I think our daughter lives in a young recipient – this is how our daughter lives.”

Both Rolly's kidneys were implanted in 14-year-old Dev Upadhyaya.

Kamlesh Upadhyaya

Kamlesh UpadhyayaThey had been waiting four years for the transplant and said that their “life has changed” because Rory's kidneys “gived new life” to development.

Rolly's liver went to a heart valve for a six-year-old boy, one and four-year-old child, and helped two adults, 35 and 71, to restore vision.

Rory's death is similar to the story of Nicholas Green.

The seven-year-old was on vacation in Italy with his family in September 1994 when the car he was traveling was shot in a case of suspected incorrect identity.

Reg Green

Reg GreenHis parents, Maggie and registration decided to donate Nicholas' organs. Reg has dedicated much of his life to a campaign to encourage more organ donation.

In 1993, before Nicholas was shot, 6.2 people donated organs in Italy. By 2006, the figure had reached 200,000.

This is due to the country's move into an opt-out system in 1999, and will become a potential donor for all adults unless otherwise stated. But bringing the idea of life-saving potential to donate to the hearts of ordinary people was perhaps the most important factor.

The Nicholas effect, L'Effetto Nicholas – is clear. The hope is that similar transformations will take place in India.

Family handouts

Family handoutsAt the forefront of this is Dr. Deepak Gupta, who traveled to Rome to meet other experts in the organ donation community.

Dr. Gupta was the first to tell Rory's parents about his organ donation options.

He uses Nicholas' example to show the possible impact of donations on the illiterate Mr. Prajapati.

According to the Lancet Neurology Committee, one person died from head injuries every three minutes, so as Dr. Gupta says, “there are many possibilities for donors.”

Dr. Gupta conducted a survey showing that factors such as religion and senior family attitudes can prevent donations.

However, since Rolly died last April, AIIMS in Delhi has had more organ donations than they combined over the past five years.

India has seen 846 donations in 2022, according to figures from the National Organ Transplant Organization. Dr. Gupta describes it as a “turning point.”

He said: “I'm quite confident – I'm a neurosurgeon, and I believe that confidence lives in my veins and blood – and that we are all born with the ability to change.

“I think it's a very small drop in the ocean trying to make a difference for people.”

Every time Reg, 94, returns to Italy from his Los Angeles home, he meets several of the Nicholas winners – on this trip he meets two women who have been linked by the transformative effects of donations.

Shana Palicera's brother David died in a car accident in March 2013, and his heart was implanted by Anna Iaquinta.

Nine years after the surgery, Anna decides to search for her donor's family and forms a strong bond with Shana. She says she's like her sister.

After driving 140km from Fondi to Rome, Shana said it was a dream to meet the “great man,” a “model for everyone.”

Anna said: “You have a lot of thoughts and you have a lot of pain on their side, so it's not easy for those who receive the heart because you feel a little unwell. But there's a lot of joy on your side, so it's like two different emotions.

“I was so happy that her family had met me, and it was their biggest surprise and greatest present.

“The biggest gift of their life was meeting me, and for me it's okay and to be with them, that's a way of saying my thanks, but thank you.

“Nothing is enough for receiving life.”

Donor data

Spain has been leading the way in organ donation for many years with the presence of full-time doctors trained as transplant coordinators in the country's largest hospitals.

“If the population is not involved, we cannot perform a transplant,” says Jose Luis Escalante, director of transplants at Gregorio Maragnon University Hospital in Madrid.

For the first time in 20 years, in 2021, the US overtakes Spain and becomes a global leader in successfully organ donation. Amid the opioid epidemic.

Italy is the ninth in the world and the UK is the 13th. In May 2020, the UK switched to an opt-out system. This made all adults automatically the organ donor.

About 300 people donated their organs under the new approach. This came two months after Scotland adopted automatic donations. Wales introduced the system in 2015.

After visiting Rome, Reg traveled to Messina to meet 24-year-old Nicholas, the son of Maria Pia Pedala, who was in coma when he received Nicholas' liver 29 years ago.

He says he will stop talking about the matter when he dies. “I'm 94, so when I first started this, I was quite old,” he told the BBC.

“I think I've cut my tonsils now, but the idea that you can save lives by speaking was a motivating idea every day.”

Additional reports from Ankit Srinivas