Table of Contents

umsom

umsomDavid Bennett, 57, says he's too sick to qualify for the human mind, but he's well on track after three days of experimental seven-hour treatment.

The surgery has been welcomed by many as a medical breakthrough that can reduce latency for implants and change the lives of patients around the world. However, some have questioned whether the procedure can be ethically justified.

They point to potential issues of moral troubles regarding patient safety, animal rights and religious concerns.

So how is transplanting from pigs causing controversy?

Medical impact

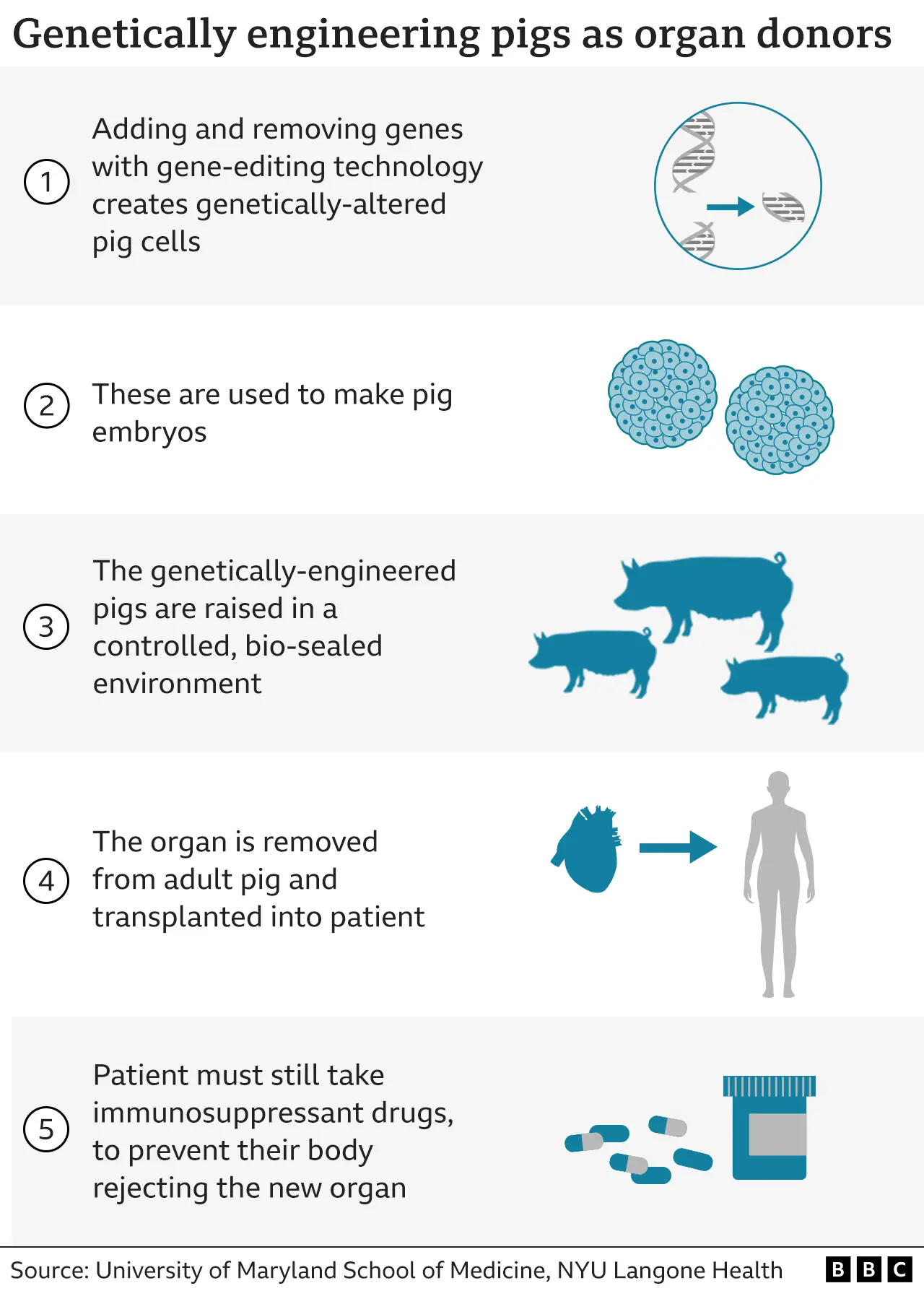

This is an experimental surgery and poses a great risk to the patient. Even well-matched human donor organs can be rejected after being transplanted, and can be at increased risk in animal organs.

Doctors have been trying to use animal organs for what has been known as xenografts for decades, and have been successful.

In 1984, a California doctor tried to save the baby girl's life by giving her the heart of a baboon, but she passed away 21 days later.

Such treatments are extremely dangerous, but some medical ethicists say that if patients know the risks, they should move on.

“We never know if a person will die devastated immediately after treatment, but we cannot proceed without taking any risks,” says Professor Julian Savursk, Ueno Chairman of Practical Ethics at Oxford University.

“I think people should be able to agree with these radical experiments as long as individuals understand the full scope of risk,” he adds.

Professor Savulescu says it's important to be given all the options available, including mechanical cardiac support and human implantation.

The doctor who worked on Bennett's case says the surgery was justified because he had no other treatment options and he died without it.

University of Maryland School of Medicine

University of Maryland School of MedicineProfessor Savulescu says that before the surgery the procedure must have been “very rigorous tissue and non-human animal testing” to ensure it was safe.

Bennett's implants were not performed as part of a clinical trial, as is usually necessary for experimental treatment. And the drug he was given has not yet been tested for use in non-human primates.

However, Dr. Christine Lau, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine, who was involved in planning Bennett's procedures, said the corners were not cut when preparing for the surgery.

“We've been trying to get this to the point where we think it's safe to offer this to human recipients for decades, in our labs, in our primates,” she told the BBC.

Animal rights

Bennett's treatment also resparked discussions about the use of pigs for human transplantation, which many animal rights groups oppose.

People at one of these, Animal Ethical Treatment (PETA), have denounced Bennett's pig heart transplant as “unethical, dangerous, and a tremendous waste of resources.”

“Animals are complex and intelligent beings, not tool skins that raid them,” Peta said.

Actors say it's wrong to change the genes of animals to make them human. Scientists changed the 10 genes of the pigs whose heart was used in Bennett's transplant, so they were not rejected by his body.

The pig removed its heart the morning of the surgery.

A spokesman for Animal Aid, a UK-based animal rights group, told the BBC it was against altering animal genes or xenoplas “in any case.”

“Animals have the right to live their lives without being genetically manipulated with all the pain and trauma that this requires.

Some campaigners are concerned about the unknown long-term effects of genetic modifications on pig health.

Dr. Catrien DeBoulder, a bioethics fellow at Oxford University, says that gene-edited pigs should be used for organs only if they can “prevent unnecessary harm.”

“Using pigs to produce meat is far more problematic than using them to save lives, but of course there's no reason to ignore animal welfare here either,” she says.

Getty Images

Getty Imagesreligion

Another confusion can emerge around people who may mean that it is difficult for them to receive animal organs.

Pigs are chosen because the organs involved are of similar size to humans. And because pigs breed relatively easily and grow in captivity.

But how does this choice affect Jewish or Muslim patients whose religion has strict rules regarding animals?

Jewish law prohibits Jews from raising or eating pigs, but receiving a pig's heart “is in no way a violation of Jewish dietary laws,” says Dr Moshe Friedman, a senior London rabbi who sits with the UK's Health Bureau's Moral and Ethical Advisory Group (MEAG).

“The main concern in Jewish law is the preservation of human life, so if this provides the greatest chance of future survival and the best quality of life, Jewish patients are obligated to accept transplants from animals,” Rabbi Friedman told the BBC.

Islam has a similar end result that if the use of animal materials saves a person's life, the use of animal materials is permitted.

Egypt's Dar al-Vida, the country's central authority to issue religious rulings, said in Fatwa that pig heart valves are permitted in the event of “the patient's lifespan, the loss of one of his organs, the deterioration or continuation of the disease, or the loss of overwhelming degradation.”

Professor Savulescu says that even if someone refuses to transplant an animal for religious or ethical reasons, it is not necessarily a low priority on the waiting list of human organ donors.

“Some people say they should go down the list if they have an organ opportunity, and others say they should have as much rights as everyone else,” he says.

“These are just positions we have to reconcile.”